by Alan Caolo

I’ve been surf-casting for many years, and in that time I’ve learned how to find success catching stripers and bluefish by properly presenting a fly or artificial lure. I choose to fish with artificials because I enjoy the challenge of identifying the available forage and then bringing a piece of wood or a clump of hair and feathers to life in a way that mimics that forage. Sometimes, however, lures just don’t cut it.

When the fish turn up their noses at the most perfectly presented artificial, their natural predatory instincts kick in and make it nearly impossible for them to resist a lively offering on the end of a line. For that reason, I’ve fine-tuned a live-bait-fishing technique that’s remarkably similar to fishing with lures or flies. Bait fishing can be much more than simply offering fresh meat to an opportunistic game fish; by keeping a fly-fishing mindset – locating prey first and then “matching the hatch” to fool the game fish – fishing live bait becomes an art form.

If I told you that I will oftentimes go bait fishing without bringing any bait along, you’d probably think I was foolish. Traditionally, live-lining entails a stop at the local bait and tackle shop to obtain bait, followed by some effort on the angler’s part to keep it alive on the way to the fishing grounds. Eels, sand worms, green crabs and, at certain times of year, bunker can be purchased alive and fished effectively in a variety of locations. The problem is that eels, worms and live bunker are relatively expensive, and if you plan on wetting a line outside of normal business hours (when the best fishing takes place), the tackle shops have already closed down. Rather than deal with such aggravation, I enjoy success by capturing the natural forage myself and fishing it right where I find it. The benefits are twofold: First, where there is prey, there are likely to be predator fish nearby. Second, you effectively “match the hatch” that the game fish are already feeding on.

Of course, Mother Nature can spoil even the most carefully laid plans, so it’s always a good idea to have a few reliable plugs, spoons, jigs and soft-plastic baits on hand. I don’t think there’s anything worse than arriving at my favorite spot and being unable to fish because I didn’t have a backup plan.

Where and When this Approach is Effective

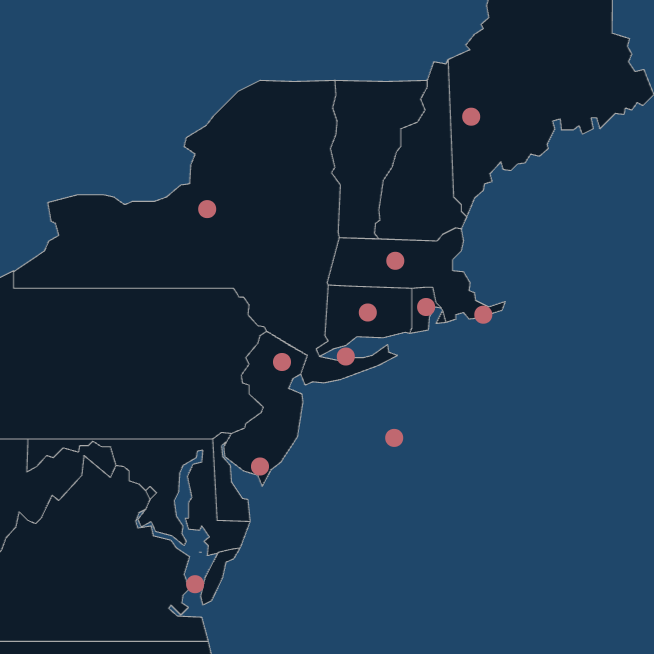

During the spring and fall, baitfish in the Northeast are bunched up and migrating north- and southward, respectively. At these times, the bait schools are easily located and a day’s supply of bait can be captured with a variety of methods. During the warm summer months, on the other hand, forage species take up residence and disperse throughout protected inshore waters, and as a result, gathering bait becomes more difficult. Catching your own bait is still a viable option – you just have to adjust your techniques.

Migratory forage fish will commonly hold around jetties, inlets and along ocean beaches. The natural boundaries created by such structure concentrate baitfish, making them easier to find and capture. A variety of bait can also be found throughout “inside” waters (bays, salt ponds, etc.), but these spots may be inaccessible to shorebound anglers.

Suitable Bait Types

Our local waters offer a wide variety of forage fish. Silversides (top) are abundant along beaches and estuaries throughout the season, and large silversides (5 to 6 inches long) make great bait for fluke, stripers and false albacore. Menhaden(middle) are also abundant throughout the region, and adults measuring over 12 inches are arguably the best livere bait for stripers and bluefish. Juvenile menhaden, or peanut bunker, show up by the millions early in the fall, serving as a staple forage food for all game fish. Mullet (bottom) appear in southern New England when water temperatures peak in the fall. They make a great bait for stripers and fluke.

Each season offers its own unique variety of prey. In the spring, sand eels, worms, green crabs and fiddler crabs are present in estuaries and coastal river systems, and striped bass are fond of all of them. These baits can be fished successfully along deep marsh banks, over drop-offs and on the flats. Along beaches, sand eels, worms and squid make up the primary forage early in the season, and all make effective baits when fished on the bottom. When using squid as bait, you can even live-line them.

Things start to get interesting in the summer, when a wide variety of prey takes up residence and spreads out along beaches and throughout inshore waters. This is both a blessing and a curse for local fishermen, as the game fish will also spread out and graze, making them more difficult to locate. On the other hand, with such a smorgasbord of baits available, fish are generally less selective and are willing to eat a variety of food. Along the beachfront, stripers, blues and weakfish feast on silversides, squid, lady crabs and worms, while in estuaries, the menu features silversides, mummichogs, green crabs, snapper bluefish, eels and juvenile bunker.

The fall season is the most effective time of year to use the live-lining approach. Many prevalent baits – including mullet, menhaden (large and small), needlefish, anchovies, silversides and sea herring – form concentrated schools as they embark on their southerly migration. Whether stalled in strong shoreline currents (such as inlets) or on the move along beaches, these forage baits attract the attention of migrating stripers, bluefish, weakfish, bonito and false albacore. Fall bait schools typically travel close to the shoreline, making them readily available for capture while at the same time drawing predators in tight.

Capturing Live Bait

There are a variety of “on-the-spot” methods for obtaining live bait. Depending on the target bait species, snag hooks, small spoons and jigs, cast nets, dip nets and even your bare hands can be effective. Many times (particularly with mullet and bunker), the bait can be captured and immediately transferred to a live-lining rig to be fished. This is generally the case when game fish are actively feeding in the vicinity. If you are not going to use the bait right away, buckets with battery-operated aerators or mesh bags fitted with a drawstring are lightweight and convenient for keeping baits frisky during an outing. Even if some of your baitfish perish, you can still-fish a freshly-dead bait. Another highly effective but under-utilized method involves hooking a freshly-dead bait through the lips and retrieving it like an artificial.

Small spoons, jigs, Sabiki rigs and squid jigs are ideal for catching snapper blues, mackerel, hickory shad, crevalle and squid. Though these small lures tend to be light in weight, most soft-tip, live-bait rods can cast them far enough to reach your target. If the bait is out of range, add distance to your cast by attaching a slightly larger spoon or jig to the bottom of a Sabiki rig, or try rigging it in tandem with smaller lures. Keep your bait-catching rigs readily accessible by storing them in heavy-duty Ziploc bags or other soft storage that fits in a jacket pocket or gear pack.

A second useful bait-catching device is an oldie but a goody: the snag hook. A treble hook, with or without lead poured around the shaft, can easily be swapped for a live-line rig after the bait has been snagged. Your best tactic is to cast beyond a dense school of baitfish and let the treble sink, then take long, smooth sweeps of the rod tip until you connect with a bait. Then raise the rod tip, keeping pressure on the struggling baitfish, and reel straight in. Sometimes it’s wise to remove the bait from the snag hook and reattach it appropriately through its mouth, back or tail, and then fish it right away. This is possible when using an unweighted snag hook (a bare treble hook, which can be cast with your rod/reel setup). Mullet and bunker are two relatively large forage species that are well-suited for this “quick change” approach. Other smaller baits, such as silversides and sand eels, are best snagged with the small spoons previously described for catching predatory bait (mackerel, snappers, etc.) and then fished – dead or alive – on single-hook live-line rigs.

Cast nets and dip nets tend to be large and inconvenient to lug around. When armed with these bait-gathering tools, the key is to find bait and catch it in good numbers early on, keeping it alive throughout the day in an aerated container. That way you can put the nets back in your vehicle and fish until you need more bait. Similarly, you can set minnow traps a few hours before you fish in order to obtain a day’s worth of bait – this is an ideal plan for fluke fishing. Whatever you decide to do, gathering plenty of bait up front compels you to keep the bait alive and carry it all day, which can be cumbersome. Cast nets work well for schooling bait of all types; sea herring, bunker, mullet, silversides and sand eels can all be captured by the hundreds. Long-handled dip nets and a quick hand are fine for smaller baits such as silversides, sand eels and anchovies.

In spring and summer, many inshore game fish such as stripers, weakfish and tautog will feed on crabs. Dip nets, rakes, and even your bare hands will suffice to gather a dozen or so green, lady, rock or fiddler crabs, all of which can be found along the edges and in the shallows of salt ponds, bays and estuaries. A small pail covered with moist seaweed will preserve crabs for hours, even on a hot day. Wet sand is another good cover if fresh seaweed is unavailable – in fact, it might be even better for keeping lady crabs. Prepare a whole live crab by removing the claws and one rear leg. Then insert the live-line hook into the crab where the rear leg was removed, and push it through so the point and barb protrude through the carapace (the crab should be dangling on the hook bend). This inflicts minimal damage on the crab and allows it to crawl about the bottom naturally. Crabs make an effective dead bait, too.

Fishing Live Bait

An 8- or 9-foot spinning rod with a soft tip (glass rods are ideal) and a reel with at least 200 yards of 10- to 14-pound-test monofilament (or 30-pound-test braided line) is excellent for catching or snagging bait that will immediately be fished on a live-line rig. This setup will easily cast the small lures, jigs, and unweighted treble hooks for catching or snagging bait, and after switching over to the live-line rig, it’s a perfect live-bait rod for targeting stripers, bluefish, weakfish, tautog and false albacore from shore. When seeking smaller, less-powerful adversaries in protected inshore waters such as harbors and bays, you might want to consider a 7-foot rod and 6- to 10-pound-test monofilament (or 20-pound-test braided line) instead.

I highly recommend circle hooks for live-bait fishing. They produce solid, long-lasting hook-ups in the corner of a fish’s mouth and minimize the chances of gut-hooking the fish. As such, they’re the best choice for sportsmen who intend to release their catch. All major hook manufacturers, including Mustad, Gamakatsu and Eagle Claw, market a variety of styles and strengths. Sizes vary widely between hook-manufacturers, so it’s a good idea to purchase your hooks from a tackle shop rather than a catalog so you know you’re getting the hook you want. For live-bait fishing, I recommend thin wire hooks. This style penetrates your bait more easily and damages it less, thus allowing it to move freely on the hook and stay alive longer than when using heavy-weight hooks.

Most live-bait hooks for inshore salt waters range from size 1/0 to 8/0. These hooks are attached to a 2- or 3-foot length of 20- to 40-pound-test shock leader via a loop knot or snell. A small barrel swivel attached to the other end of the leader facilitates attachment to the end of your fishing line when you are making the switch to a live-bait rig. A loop at the end of your line or a snap swivel is key to this type of fishing, as it enables a quick switch from the bait rig to the live-line rig. A snap is certainly advantageous for swiftly switching back and forth between the bait/lure and live-line rig (it must be light and small enough to attach the very small lures sometimes used for capturing bait), but a plain loop is best when employing egg sinkers, as described below.

Once a bait has been obtained, I switch to my pre-rigged live-line rig, attach the bait, and fish it with no weight. Most bait will seek its preferred depth anyway, and added weight often causes the bait to struggle and die more quickly. As such, fishing a live bait without the encumbrance of added weight is the most deadly approach you can take. Furthermore, most shoreline fishing takes place in relatively shallow water (less than 12 feet), and even a live crab will make to the bottom in 10 to 30 seconds. When fishing in excessive depth or current, however, additional weight is necessary to get your bait down in the water column. I recommend egg sinkers. Small eggs ranging from ¼ ounce to 1 ounce can be slipped over the loop on the end of your line before you loop on your live-line rig. These sinkers provide enough weight to get your bait down but don’t inhibit your bait’s liveliness.

Live-lining your bait can be executed many ways. Still-fishing, casting and retrieving, swinging it in the tide, free-spooling, and “walking it” with the current are all effective methods. When fishing bait on the bottom in calm waters, still-fishing is my preferred technique, such as when using a crab for tautog or striped bass, or a squid for stripers or blues. In the surf, I like to slowly retrieve the bait, often letting it swing or move with the wash and just keeping the slack out of the line. When fishing a mullet or bunker (secured through the lips), this presentation can be deadly even after the bait has perished and wiggles no more. Think of it as slow-fishing an artificial, one that is as natural as it gets. The strikes are jolting! When bait is swept or moves with the tide, a natural presentation would be to mimic this and allow the live bait to “go with the flow.” In addition to appearing more natural when alive and kicking, a small live bait, such as a silverside, will still draw strikes after death, as it flutters seductively to the bottom.

Free-spooling is effective when fishing large baits that game fish need time to swallow. This entails keeping the reel in free spool after the cast has been made and excess slack line has been reeled in. Keeping the reel in free-spool enables a quick release of tension (often in combination with a drop of the rod tip) when a fish takes the bait.

When fishing live bait in channels, inlets, breachways or other relatively deep, current-laden waters, I prefer to “walk the bait” with the current. With this method, the bait is cast slightly upstream and allowed to settle. After slack is removed, simply walk along with the current while staying tight to the bait. This allows the bait to reach the preferred depth while achieving a natural and effective presentation. It also lessens the strain on your bait that comes from constant casting and retrieving.

What about utilizing snaller blues as a live line for strippers??

it works

Very informative. Would love to see more articles like this. Not everyone is an expert. Thanks for taking the time to educate we neophiytes.

[…] as closely as possible to the fish’s natural foods — at least to begin with. After all, such a fly will innately trigger a predatory response, thanks to millions of years of […]

Some live bait fishermen have problems keeping live bait healthy and alive in the heat of the summer, most fishermen never have any summer live bait problems because they never overcrowd their livewells.

Some hard core live baiters fishing summer tournaments for $$$ Supercharge their bait fish, this is how “Supercharging” works when you want an abnormally active live bait.

Supercharging Your Live Bait – http://www.georgepoveromo.com/content.php?pid=64

By the way, this is very unnatural in the normal livewell environment. Any live baiter can make an exceptional bait fish like this.

Jibe