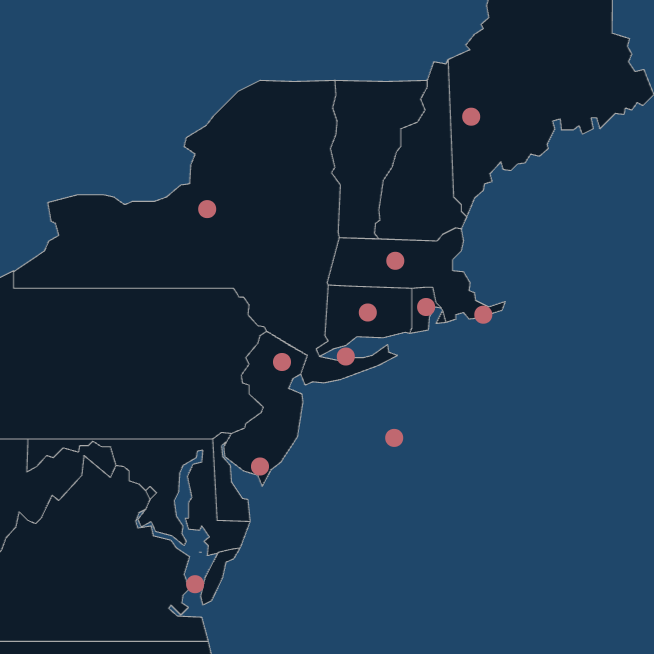

The scene of a bluefin research sampling site to determine the origin and age of tuna living in the Gulf of Maine.

“That’s why they have tails.”

It’s an oft-spoken lamentation among bluefin tuna anglers upon arriving at a spot that was bursting with life the previous day but transformed into a biological desert overnight. As a highly migratory species, bluefin present a challenge not only for the anglers who target them but for fisheries scientists.

Since the early 1980s, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) has assessed and managed bluefin tuna as two separate stocks: an eastern stock that spawns in the Mediterranean Sea, and a western stock that spawns in the Gulf of Mexico. A key assumption with this management structure is that all fish encountered off the east coast of the U.S. are from the western stock. The problem is—no surprise here—that bluefin tuna have tails.

“While we have this two-stock construct, we understand that a lot of fish pass over the arbitrary boundary in the central Atlantic, although fish return to their respective spawning grounds to reproduce,” explains Dr. Lisa Kerr, a research scientist at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI) in Portland, Maine. Although neither stock is currently believed to be experiencing overfishing, the western stock is only about a tenth of the eastern stock’s size. As a result, understanding the degree of mixing from the east—the “subsidy” of Mediterranean fish into our waters—can really influence the perception of what’s happening with the western stock. “Tracking each population is like an insurance policy for the fishery,” Kerr says. “We don’t want to have all of our eggs in one basket by relying on just one population to exploit.”

Determining the Origin and Age of a Bluefin Tuna

To determine the stock composition of Gulf of Maine bluefin, Kerr and her colleagues at GMRI, the University of Maine, the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, and the University of Maryland analyzed otoliths—ear bones—from nearly 800 fish caught between 2010 and 2013, with most between 60 and 100 inches curved fork length. In addition to being useful for estimating age, an otolith can be used to determine a bluefin’s natal origin because the chemical composition of the otolith core—specifically, ratios of stable carbon and oxygen isotopes—differs between the Mediterranean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. While the chemical analysis is a delicate process, the process of extracting the dime-sized otoliths isn’t, with scientists employing a hacksaw or even a chainsaw to slice into the center of a 100-pound tuna head. The team relied heavily on donated tuna heads from commercial and recreational fishermen for this research. “They’re always fascinated to hear about what we can learn from a part of a fish they would otherwise throw away,” says Kerr.

The researchers found that the vast majority—as many as 85%—of the bluefin tuna sampled off New England were not of western origin, but in fact came from the eastern stock. While the exact percentage varied by 10% to 20% annually, eastern fish were far more commonly encountered in each of the four years of sampling. “Fishermen are always astounded to hear that a high proportion of fish we find are coming from the Mediterranean Sea,” says Kerr. “But when you think about the relative abundance of the two stocks, it kind of makes sense.” And, after all, with the Gulf of Maine’s rich productivity that attracts herring, mackerel, sand lance, menhaden, and host of other prey species, it’s perhaps no surprise that for an eastern-born bluefin, a transatlantic journey is worth the trip. Interestingly, among the largest fish in the sample—giants over 100 inches—the split between the two stocks ranged from 50/50 to predominantly western-origin fish, perhaps since the Gulf of Maine is relatively close (in bluefin terms) to the Gulf of Mexico spawning grounds.

New Bluefin Tuna Management Approach

Kerr and her colleagues’ findings represent the most recent contribution to a large body of research investigating bluefin tuna mixing using a variety of methods, including tagging, genetics, and persistent pollutant analysis, in addition otolith microchemistry. To date, however, none of the science on mixing has been incorporated into management, and bluefin are still managed as separate, noninteracting stocks.

But, that won’t be the case for long. This work will inform a new management approach for bluefin tuna called Management Strategy Evaluation (MSE), in which scientists simulate how a fishery operates in order to influence the development of management actions, known as Harvest Control Rules, that will automatically be taken depending on stock status. Scientists developing the MSE, including Kerr, are working to incorporate mixing of eastern and western bluefin tuna into their scenario testing in order to portray the fishery more accurately. While plans to implement MSE have been delayed due to COVID-19, managers hope that it will be ready for action in 2022.

A critical element of the MSE is not only considering current mixing rates but how changes in ocean conditions could impact future mixing. “We know that there are a lot of distributional changes happening right now with bluefin tuna due to climate change,” Kerr explains. “Through our continued otolith collection and analysis work at GMRI, we will be able to determine how warming in our part of the ocean may be impacting the relative abundance of eastern versus western fish, and then we can update our models accordingly.”

Related Content

More Focus on Fisheries Articles by Willy Goldsmith

Article: Identifying Bluefin vs Yellowfin Tuna

Article: Bluefin Tuna Chunking

Article: Jigging for Bluefin Tuna

Article: Bluefin Tuna Tagged to Fight Another Day

Great article! Thank you again OTW. Always, with the newest and clearest knowledge we can help the fishery and the BF giants to survive and propagate. Not being selfish and increasing the stock is always the best foot forward. Hopefully with this data we can keep the world’s BF tuna stocks from being overfished. I don’t appreciate when I see fisherman across the pond netting them by the 100’s and hopefully data like this can prove to be helpful.

Good thing Trump is outta there- if he heard this he probably would want to build a sea wall to keep out those eastern tunas.

Yeah and Biden will tear the wall down and allow in all COVID infected fish