My father taught me how to scallop—how to bay scallop, that is, a critically important distinction, I would learn—right here in a Wareham bay between Swifts Beach and Long Beach at low tide. I was 12 at the time, and the scallops all those decades ago were plentiful prior to the brown tide, a toxic algae bloom that caused devastation in the 1980s. At that time, overharvesting wasn’t a term used too often. Folks tended to fish to their limits, or more.

One morning, my father and I were in a small powerboat hauling a scallop drag off the stern. It was the first of November, and I was freezing cold.

“Pull it straight up and try to keep it from hitting the side of the boat,” Dad ordered. “As soon as you empty it, throw it back overboard.”

He was the captain and I was his crew. This was typical of his terse, nautical commands. He steered the boat while I worked the steel mesh drag up and down throughout the afternoon, raising the bag to the boat and unloading it on a plywood workstation to cull. Rocks, empty shells, eelgrass, starfish, mermaid’s purses—a marine Mulligan stew—were tossed over the side of the boat, leaving what we were after … bay scallops, and lots of them. Our tandem effort was productive – we would have the bushel basket full in short time.

Bay scallops—Argopectem irradians—are bivalve mollusks of the family Pectinidae. They exist here in Atlantic waters, all the way from Texas and Florida to the Northeast, and grow up to four inches wide during their two-year lifespan. They consist of two asymmetrically rounded halves called valves (an eye-pleasing architecture that is the subject of many a motif), joined together by a ligament called a hinge.

And, they are delicious. Bay scallops are so sweet and succulent, in fact, and so good for you, that they may be considered one of nature’s perfect foods.

My father, then a school principal and a U.S. Navy veteran, was passionate about the taste of scallops. I’d finish each cull by pushing the scallops into our peach basket with my forearm. In turn, he’d let go of the wheel, shuck a couple on the spot and down them raw.

“Like candy,” he’d say with authority. “Nothing else like them.”

My tastes were less sophisticated then. The idea of eating something so fleshy, so viscous-looking, was repulsive. I declined repeated offers to join him in slurping down the uncooked fare.

He was equally passionate about the process of going after bay scallops. Each fall, while waiting for the November harvest season to begin, he’d scan the shore for telltale signs that the scallops had arrived. Small boat activity was one such sign. Seagulls extracting them from shallow water and breaking them open by dropping them on hard rock and asphalt surfaces was another. When his work schedule and the tides aligned, he’d be out the door.

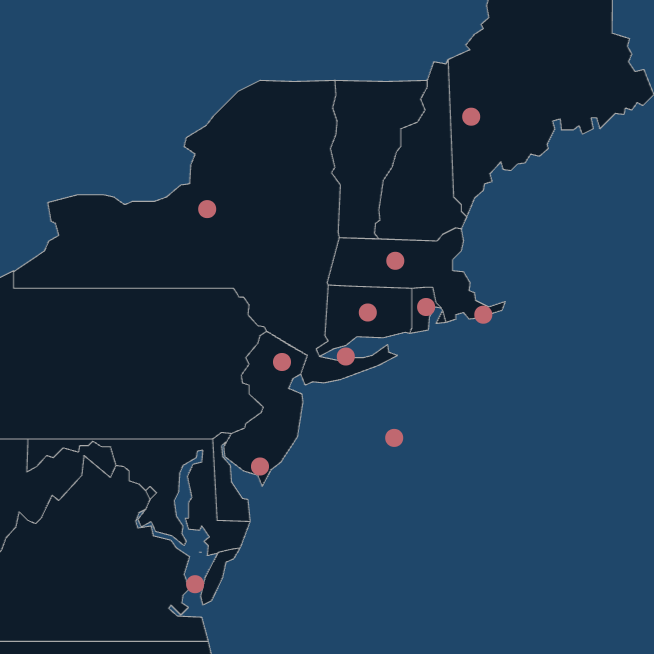

There are three predominant kinds of scallops harvested in the U.S. for commercial purposes. The trio includes bay, calico and sea scallops. By far, the sweetest of these are the bays. Prior to the brown tide scourge in the eighties, scallops would ride currents into protected bays, inlets and estuaries by the thousands. Knowing that bay scallops prefer to cling to eelgrass during their larval process, scallopers knew just where to look and were all but guaranteed a quick bushel. When toxicity depleted the eelgrass beds, and shark killings rose (e.g., sharks eat stingrays, stingrays eat scallops), the bay scallop population suffered. It took many years of Mother Nature’s healing and human aquaculture efforts to turn this around. Right now, in the fall of 2012, there are scallops lying in northeastern bays, though less abundantly than in the heydays my father enjoyed some 40 years ago, but enough to make the effort worth the reward.

The adductor muscle inside the bay scallop is what devotees are after. Surrounded by viscera, the muscle meat is firm and translucent, ranging in color from ivory to pinkish-white. Shaped like the cork of a wine bottle, it is this adductor muscle that gives the scallop swimming power. With the ability to open and close its valves rapidly, the scallop can travel for business (to avoid predators such as sea stars, crabs, and whelks) or pleasure (change of scenery). Bay scallops are not distance swimmers, tending to propel themselves backward only in short bursts of speed over small distances. Their longest trips occur in partnership with ocean currents when they are young. They can see, albeit weakly, through some 40 cobalt-blue eyes visible on their mantles.

My father and I would spend about three hours on the water, dragging back and forth over a swath of sea about 100 yards long and 100 yards wide. My father concentrated on avoiding collisions with other working boats and took care not to get too close to scallopers wading offshore with homemade viewers of plywood or Plexiglas. These viewing devices allowed scallopers in waders to walk in the shallows and locate their prizes one by one; handheld nets allowed them to scoop up the scallops. In waters slightly deeper were the snorkelers. Dressed in wetsuits, their handpicking methods were similar, but they had to be willing to get wet. The water was alive with all this activity. Somehow, the three species of scallop fishermen – boaters, waders and snorkelers – found a way to exist harmoniously.

Bay scallops have the remarkable ability to develop both female and male sexual organs. Hermaphroditic, a single bay can produce both egg and sperm. It takes 36 hours for an egg to become larvae; thus, survivors in such a dangerous and hostile environment are scarce. Only one out of twelve million makes it to adulthood. The lucky ones that survive begin their days as larvae. Young bay scallops are pelagic at this stage in their life, meaning they reside in the middle of the water column rather than on the bottom where they are found when grown. They ride the currents here and there, drifting without any say in their destination, for about two weeks. During this time, they transform into juvenile scallops. These adolescents are called spat.

Adolescence may breed impulsivity. When eelgrass looms in sight, the spat grab hold of it via byssal threads—nature’s own Velcro—and remove themselves from the arbitrary ocean streams. Having already seen the world at a young age, they now decide to stay put. Although ninety percent of all spat will die within the next few weeks, those that survive eventually drop to the bottom and will stay in this general area for the remainder of their short lives. If the scallops and the water in which they live both stay healthy, they will reproduce and sustain their own population in this same general area. Scallopers are driven to find these permanent homes, but there are no guarantees of success. This randomness explains, in part, why scallops seem to be in a particular location one year and gone the next.

My father enjoyed being outside on the saltwater. The sun, spray of the sea and cold breeze were a tonic for him. He was able to remove himself from the stress of running a public school and immerse himself in a simpler and more tactile existence. He didn’t put into words the joy he felt when he was out there, but you could sense it. He was more relaxed, more comfortable in this environment than in any other.

Once caught, scallops had to be shucked. Happily, I was relieved of this duty. For my father, it represented another step in the wonderful process. We’d arrive home, proud hunter-gatherers bearing the day’s catch, and my mother would join him in the garage to shuck. Lots of beer drinking and more bays eaten raw ensued. The result was a heaping mess of empty shells and guts, which my father hauled down to the coastline and dumped. The crabs saw this as a free buffet and swarmed over it.

A bay scallop is a filter feeder, and will open its valves to take in algae and organic matter from the water. This purposeful opening, along with the occasional swim, are the only times a scallop will flap its valves. Out of water, it may open just a bit, and then quickly snap shut in an effort to breathe. Shuckers look for this slight opening and insert a curled-tip knife because a bay scallop that shuts can remain closed for up to two hours. This usually requires the shucker to penetrate the valves near the hinge. It is not difficult work, but it is labor intensive.

The skill of shucking involves placing the scallop dark or dirty side up (one side usually appears lighter and cleaner than the other) and lifting one valve away from the other far enough so that a knife can slice the adductor muscle. A wresting match ensues as the bay scallop flexes its adductor and attempts mightily to clam up. The shucker’s fingers are on the receiving end of a force that is evident, but does not really hurt. The knife tip curls to conform to the concavity of the shell, thus producing the least amount of waste.

Once the adductor has been cut away on one side, the work gets down and dirty. The shucker uses a thumb to place the viscera (gut, mantle, gonad, gills, eyes, and heart) between his index finger and the knife, and it can be removed cleanly in one fell swoop. Done correctly, you will be looking at nothing but a gleaming white adductor muscle ready to be dropped into a pan. Do it incorrectly and you must pick away at all this gooey stuff that just does not want to let go. Either way, the feeling is similar to catching a thick, gigantic sneeze in the palm of your hand. Europeans, by the way, flour, fry and eat the adductor and viscera together. While I have seen seagulls do this, I have no personal knowledge of any human in these parts who has dared.

We are lucky here in southeastern Massachusetts. Bay scallops were here, left for a spell, but have returned. While the bulk of scallops eaten in the U.S. come from China and Japan (aquaculturists there grow them in suspension nets, negating the harm done to bay bottoms by drags), a small amount of them come from premium scallops obtained in New England. Our bay scallops have cachet and are considered the best available in the country. To wit: a pound of farm-raised Chinese scallops presently costs $5.99. The same weight of local bays will run you $29.95 (the difference being a reflection of quality and demand). It is no small surprise that when the Chinese first began experimenting with growing their own scallops on marine farms, they came to Cape Cod and took live ones back to Asia. So, while most Americans may be eating Chinese scallops, their origins came from our own backyards.

All scallops taste good, and indiscriminate diners devour them blissfully ignorant of their species. There are about a dozen species commercially important, with three representing the greatest availability in the U.S. Bay scallops are one. Calico scallops and sea scallops are the others. Locally, the seaport of New Bedford can lay claim to the largest bay scallop catch each year. Further, the bay scallops harvested in Nantucket waters (with adductors a bit bigger than bays found anywhere else) are generally considered to be the most desirous in the world.

The valve size of a calico is smaller by an inch than their bay relative. Calicos live in the Atlantic Ocean, not in bays, and are caught by trawling with heavy nets. Their shells are mottled prettily, with splotches of bright lavender and maroon. They are more stubborn than bay scallops, and must be steamed to open their shells for shucking; they also are not as sweet as bay scallops. The health of their population is suffering lately and there is not an abundance of them on the market.

Sea scallops, with a life span of 20 years, live in the northwest Atlantic Ocean from Newfoundland to North Carolina. About the size of a marshmallow, they are the biggest and plumpest of the three. These are the most common type of scallop served at restaurants. They taste delightful, like the sea, but are more bland than their little brother bay scallop. One pound of sea scallops can be purchased for $14.99. Caught by commercial trawlers, they are shucked onboard and stored on ice.

Put a bay scallop in your mouth—lightly sautéed or broiled—and your taste buds explode into action. It is moist and tender, with a composition that leaves you able to swallow at the very first bite. No seasoning is needed. They are rich and redolent, briny and sweet. This nectar-from-the-sea taste was summed up in a word when my father described them as “candy.” To say that bay scallops have a distinctive flavor is making an understatement. They are simply complex. Take one from the water, shuck it, and sear the adductor in butter for maybe three minutes. It is caramelized on the outside and soft within the center. Put it in your mouth and you’ve reached gustatory heaven.

And there’s more to the bay scallop deal than taste. Four ounces of the muscle meat—a good serving size—contains just 100 calories. They have a high protein value and rank low in terms of saturated fat content. Rich in vitamin B12 and omega-3 oils, the scallop is considered a “miracle food.” Some evidence shows that joint pain, migraines, depression and autoimmune diseases can be alleviated by consuming these vitamins, which the bap scallop just happens to contain. It is thought that omega-3 oil also improves memory functioning. The real miracle may be that something so fine tasting is also good for you.

Since scallops are filter feeders, they can collect harmful toxins, bacteria and pollutants within their tissues. The good news, however, is that the toxins accumulate in the digestive tract rather than the adductor muscle portion we eat. Furthermore, cooking kills any dangerous bacteria that may exist inside the scallop.

Back to my childhood scalloping days … once the scallops were shucked, it was time to eat. My mother and father, with stomachs not yet full from the couple dozen they had eaten raw, switched to a fried version. The scallops were dried (always an important step to rid them of water to prevent them boiling rather than frying), then coated with flour, egg and a dried batter mix. A hot skillet of oil was used to deep-fry them. They were then eaten as-is, or with tartar sauce as a condiment. I ate these too, as a kid, and remember the taste and texture as if it were yesterday. To this day, I like fried scallops now as much as I liked them then. Scallop casseroles and broiled recipes followed in family suppers thereafter. And scallops freeze well so the November-caught shellfish could be eaten in May.

Shucking A Scallop 1. The skill of shucking involves placing the scallop dark or dirty side up (one side usually appears lighter and cleaner than the other) and 2. lifting one valve away from the other far enough so that a knife can slice the adductor muscle. 3. A wrestling match ensues as the bay scallop flexes its adductor and attempts mightily to clam up. The shucker’s fingers are on the receiving end of a force that is evident, but does not really hurt. The knife tip curls to conform to the concavity of the shell, thus producing the least amount of waste.

Once the adductor has been cut away on one side, the work gets down and dirty. 4. & 5. The shucker uses a thumb to place the viscera (gut, mantle, gonad, gills, eyes, and heart) between his index finger and the knife, and it can be removed cleanly in one fell swoop. Done correctly, you will be looking at nothing but a gleaming white adductor muscle ready to be dropped into a pan. 6. Do it incorrectly and you must pick away at all this gooey stuff that just does not want to let go. Either way, the feeling is similar to catching a thick, gigantic sneeze in the palm of your hand. Europeans, by the way, flour, fry and eat the adductor and viscera together. While I have seen seagulls do this, I have no personal knowledge of any human in these parts who has dared.

There may be more recipes for scallops than there are calicos left in the ocean. Google “bay scallops” and the problem becomes one of indecision. Newberg-type recipes include butter, flour, salt, paprika, milk and sherry. Italian versions involve pepper and onion, garlic, olive oil, tomatoes, lemon juice and white wine. There are sauces to pour over baked dishes. There are Japanese sashimi and sushi preparations—raw or cooked scallops appear with rice and vinegar. The lists of recipes go on and on. Through them all, however, there is one common theme evident in bay scallop cooking instructions – they need only two or four minutes of critical heat. Overcooking is a losing proposition, as the scallops will become tough and fibrous. Skilled chefs note the active verbs of “simmer gently” and “sauté lightly.” There is no need to push the envelope on one of nature’s most sublime products.

I am now my father’s age when I went on my first trip with him. Not long ago, I went out scalloping with my wife and daughter. We were boat-less, so we shared a viewer and, dressed in full wet suits, snorkeled in turn. We were neck deep in water off Stony Point Dike, the peninsula of land that represents the beginning of the west end of the Cape Cod Canal. I found myself passing along tips I had learned from my father.

“You have to look carefully. They don’t call you when you are in the neighborhood. They blend in with the eelgrass as a form of protection from seagulls. And keep moving around. Try to cover as much area as you can.” I was the captain and they were my crew. These were the nature of my nautical commands.

We all found scallops. Many dozens, in fact, that we carried in catch bags. The cold water felt good and, now being a school administrator myself, I understood my father’s obsession with the hunt.

Later, my wife invited my father to our house for dinner. She went gourmet on us, making polenta from scratch, and using it as a base for tomato, heavy cream, white wine and, of course, the bay scallops. My father doesn’t eat large portions of anything anymore, but he had no trouble eating the whole of this dish.

“Tasted excellent,” he said afterward. “But you didn’t have to go through all that work. Bay scallops really don’t need any help. They are good just as they are.”

Excellent article Dave. Hope to see you out there soon-another school administrator and Wareham native!

I agree! Excellent article. I’ve done all the other shell fishing but not scallops. I’ve seen people out in that area you mentioned. I shell fish and fish there. I hope to give this a try!! Happy scalloping!

Great articial wish I had someone to show how to do it,

and how and when to hunt for them

Thank you for an excellent article. God Bless the scallop fisherman, so I don’t have to do the work. They are good raw, steamed, or fried but best in casseroles with some bacon, cheddar cheese and a little bread crumbs.

like to know when, where and how. Great article. Any size limit like them with bacon, more bacon

Nothing better than fresh bay scallops that you have caught. My opinion don’t mask there flavor, just sauté in butter for a minute to get a little browning. They are so sweet all they need is a cold beer

Very nice article, Dave. I am just about ready to put my 4 drags away across the Canal in Bourne. I am getting too old to pull them by hand and View Boxing is more fun. We are only having a fair scallop year but the work is well worth it. What struck me in your article is that it is indeed an activity where my adult son and I also can spend quality time together.

anyone know of any bay scallop guided day trips?

Excellent read, in depth, informative and fun. Thanks, I learned a lot reading your work-gb

Thanks for a great article. Very informative especially for the newcommer. Just finished up shucking a hundred or so Nantucket scallops for the freezer. Thanks again very enjoyable reading.

Great article, Dave. Are licenses required in Mass.?

I have similiar family memories of digging clams and quahogs back in the late 50’s , 60’s in Apponaug (Warwick) R.I. but never did scallop digging. My grandfather, in his 70’s then, would follow the tide uncovering soft shelled clams without EVER breaking their shells. I never got the hang of it so the rest of us gathered the quahogs for chowda and clam cakes! Frustatingly, can’t find those great foods down here in NJ!

I’ve been down here in NJ for decades….. and you’ve whetted my appetite- recently retired, if you’re aware of any recommended “spots” along the “Jursey Shaw” I’ll give it a try!

Reading thsi in Buffalo…Great article and great memory of us out scalloping that fine October morning. How I miss those days

Hi Rob,

Long time no hear. Your quahog rake is still working fine, although a bit rusty at this point.

Next time you are in town please call.

Dave

This was a fall ritual for my family…my parents would join their friends for the opening of the season on the vineyard. it was a fall weekend of shellfishing, shucking and drinking.

When my parents moved to the cape in the 80’s, we would join them on this weekend and all of us would scallop opening day, we’d be there when the sun came up, and we’d be home by noon. We’d all sit in a circle shucking, those unskilled with the knife would bag the meat and the shells. Making your bags of frozen scallops last the entire winter was an exercise in self control.

any good places in NY or LI sound to look for them

My brother lives in Chatham Ma and this year he got a shellfish licence.

He’s been clamming, crabbing, musseling and fishing all his life on Chappaquiddick but has never gone scalloping. I wonder if readers can recommend the best waders for this activity…? and any other equipment tips. I want to get him some waders for Christmas. maybe I’ll dig out my old shucking knife as well. I shucked them for a small wage back in the day in the sheds of Chilmark and Edgartown and I will agree with those that eat them raw, soooo good!!!!!

slow cook in the oven with any garnish that fancies your pallet.. here on nantucket it’s called a “casino”.. hence the results.

I would like to know if any towns on the coast of conn allow scalloping and their regulations on harvesting. Thanks paul

Thanks for this article. I’m in Midland, Tx and it makes me homesick. Will be back in June of 2016.

I’ve spent many summers on Martha’s Vineyard. One summer in a kitchen full of people, it took them 20min of begging for me to eat a raw scallop. I finally gave in. Oh my God, I thought I died and went to heaven. It was like butter melting in my mouth. I’m with your Dad on that. Just heaven!

[…] Bay Scallops Read our post for great tips covering everything from finding to shucking these delicious bi-valve mollusks. […]

Dave,

Hope you get this… ‘member me… Bradford College… 1981… I found some letters in my attic & came across a reply from you 9/5/83. Thought I’d look for you & Sue on the http://WWW... I came across this article and knew for sure it was you by the close up picture of Sue & your daughter. If you do get this… we can try emails or call to say, “Hello”. Give my regards to Sue.

Hello Frank,

Just saw your comment on my scallop story. Very enthused to hear from you. Also very pleased that after all these years you recognize us. Hope everything is going well for you. Sue and I live in Wareham, Ma. and are now retired from education careers. I am in the process of starting an oyster farm here in town. Where are you now and what have you been up to? Hey, going to Barbados soon and am trying to get in touch with John Ward. Do you have any telephone numbers or addresses I might try for him?

Dave and Sue Paling

I wou;d like to buy 50 pounds of shucked bays

Hi Dave,

I came upon your article while reporting on a radio story that I’m pitching to GBH News. I also freelance for The World radio and was interested in your reference: “It is no small surprise that when the Chinese first began experimenting with growing their own scallops on marine farms, they came to Cape Cod and took live ones back to Asia. So, while most Americans may be eating Chinese scallops, their origins came from our own backyards.” Can you share with me where you learned this>? Do you know anyone who might know about this and when it happened? Thanks so much. Rachel

I as well first stalked the blue eyed scallop in Wareham. My grandfather retired in 1971 and moved to Wareham. I was 12 years old and spent many a day with grand pa digging for Quahogs. a by product was that we picked up a scallop or two along the way. My grandfather unfortunately passed away in 1971, my dad caught the bug and we continued to shellfish in Wareham. Our scalloping adventures were comical at first. We would drag a Quahog new through the eel grass and pick up a few . Eventually we observed others and built view boxes.

I spent a lifetime perusing sweet bay scallops in Falmouth. Yet my origins were in Wareham. A funny story: when my now 30 year old son was in second grade he missed school on October 1st opening day. His teacher was shocked he took a day off to catch shellfish. Dan simply replied “its a holiday in my house!!!

I have now retired to Wareham. I’m looking to re visit my childhood so will try my fall pastime again. Thanks for reviving the memories.