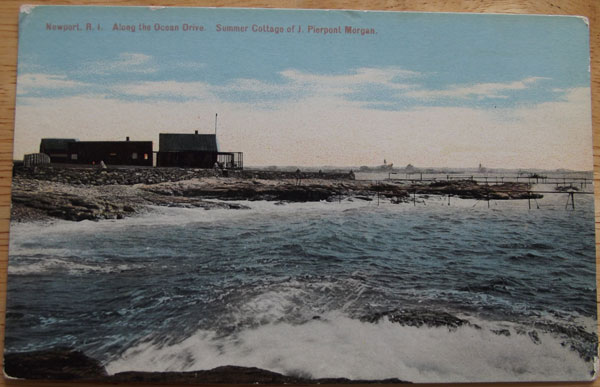

Pictured above: Gooseberry Island is prime striper habitat with numerous rocks, reefs and washes. There were at least two bass stands on the east and southeast corner of the island where the author still catches quality stripers.

Our introduction to the “secret spot” along the frothy rim of the open ocean began on a huge rock marked with a collection of twisted and rusted pieces of bent pipe and the stained remnants of holes that appeared to have been hand-drilled into the surface of the rugged granite. That was more than 50 years ago, when my friend Russ’s Uncle Arthur transported us away from the hunt for schoolies in the rivers and the lower bays to the wide-open ocean along Newport’s Ocean Drive.

The 10-mile drive is famous for its uber-wealthy residents and the mansions they built in the era before income taxes. Little did I know that I shared the same interest as those men from Millionaires’ Row—the pursuit of trophy striped bass.

-Photo Courtesy of Kib Bramhall

I was familiar with using a heavy star drill, a bucket of water to cool the bit, and a three-pound sledge to make a hole in a chunk of mooring granite that could hold a heavy, galvanized eye bolt. On occasion, it took two days to drill through a single slab, so it was obvious to me that whoever drilled that many holes spent a lot of time there on the extreme low tides. However, I had no idea why those pipes were there and, at the time, I had no idea that we were fishing on sanctified striper grounds.

It wasn’t until years later that I learned of the significance of those rusted pipes at the ocean’s edge when I met with the elders at the Sakonnet Point Fish Trap house. Several of them had relatives who had been employed at the West Island Club, located just a short distance from Sakonnet Harbor. One of those historians was in his late 70s and boasted of an aunt and uncle who worked at the club for quite a few years in the late 1880s, she as a maid-cook and he a chummer-laborer. He shared their tales of the members and guests of that exclusive club, giants of industry and politics, and their tenacious pursuit of striped bass. He also relayed stories of watermen and farmers who worked there for hard cash, including two lobstermen who wore thick leather gloves while drilling holes in the island granite to make foundations for the pipes that supported the slats and ropes comprising the “bass stands” over productive striper habitat.

The West Island Club

The West Island Club officially opened in June of 1865, exuding “primitive comfort.” The club had a total of 12 named bass stands, with the preferred locations being on the south and southeast sides, facing into the prevailing southwest winds; however, there were seldom more than eight members fishing at any one time.

Invitations to the West Island Club were few, and regrets were unheard of. Once on this distant island outpost, guests were rewarded with gourmet food, refined company, and great fishing. However, getting there was a major challenge. Arriving in Newport by steamer or train was only the beginning of the journey. The long, dusty carriage ride over bumpy roads could take the better part of a day. Yet, despite the difficulties and discomfort, guests came from New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington DC.

The member with the shortest commute was Cornelius Vanderbilt, who could sail his yacht and make the trip from Newport Harbor to the cove on the northeast corner of West Island in a little under an hour.

The West Island Club kept detailed records of every day of fishing, including the number of fish and their collective weight along with the name of the angler and the stand from which the fish were taken. Philo T. Ruggles, one of the most intrepid anglers of the day, was a New Yorker who held records for the largest striper (a 64-pounder on August 13, 1877) and the most stripers taken at the club in a single day (87 stripers on July 19, 1876).

The club members’ tackle was the best available during that era, but it left much to be desired in pursuing outsized stripers in their rocky lairs. The long, 12- to 15-foot rods were constructed of bamboo, split bamboo, or greenheart (a solid cylindrical-shaped rod), and the reels were made of wood. The materials were subject to warping, but there were primitive corrective heating remedies for that. The only drag was a leather thumb stall, which also served as a brake to prevent backlashes during the cast. Because money was never an issue, the members, particularly those who had direct access to tackle vendors and sporting goods merchants in New York, were always petitioning the tackle manufacturers for improved fishing gear. By late 1885, club members were fishing with Vom Hoffe reels with German nickel silver braces, hard rubber side plates, and improved linen line.

The club and its members prospered until the persistent decline of striped bass began to take its toll. Catch records for 1874 indicated a total of 2,406 stripers with a weight of 11,356-pounds—a good year indeed. The numbers thereafter were anything but encouraging—with only 22 bass landed in 1886—causing numerous members to withdraw, leaving too few to continue the operation as intended. The end came in December 1906, when the directors put the land up for sale. Member Joseph R. Wainwright purchased the holdings and converted it into his family’s summer retreat. The precipitous decline in the striper population prompted similar scenarios at other principal striped bass clubs.

The Cuttyhunk Bass Club

The Cuttyhunk Club was a prime yet more problematic location to access, but for a group of very affluent individuals, that was hardly a deterrent. Most of the new club’s land was purchased from the Slocum family for what was to become the Cuttyhunk Fishing Association, later shortened to the Cuttyhunk Bass Club.

After the initial purchase of shares, members were required to pay annual dues of $100, but they were not charged for their rooms. Guests were charged $3 per night. While the pursuit of striped bass was stated as the primary goal, men of this class were accustomed to elevated levels of comfort and luxury, so their time on the island could not be considered roughing it.

Seven former members of West Island brought on friends and associates, eventually reaching a total of 75 members who purchased individual shares for $400 each. Those funds were used to construct buildings, build 16 fishing stands, maintain grounds, and hire local staff to operate the club.

Records show that John Lynes caught the first recorded striper on June 18, 1864, and went on to record fish of 49 pounds as well as the single largest total of 33 stripers in one day. A few of those bass stands were engineering feats for the time, extending more than 150 feet from the beach. You had to be a fearless individual to climb the perches hovering over the wave-swept boulders on the south side of that rugged shoreline.

Fishing along the south side of this tiny atoll was extremely productive, and in 1865, the club’s first full year of operation, 50 members and guests fished a combined 556 days, catching a total of 1,252 stripers. Over the next 30 years, fishing success fell off, not due to a lack of effort but the precipitous decline in the striper population.

As the quality of fishing deteriorated, the political climate on the island began to worsen. Native Cuttyhunk residents were a tough and resilient lot, as anyone who chose to make a living on a small, remote island had to be. The club continued to increase their land holdings, and at one point, they owned 466 acres of the island, leaving only 15 acres in private hands. That affected almost all phases of daily life on this once rustic and remote community. To make relations even more difficult, the club prohibited farmers from gathering seaweed for fertilizer and controlled all lobstering and fishing along the shore. Another bone of contention was that the club prevented the islanders from fishing from club stands. In order to legalize their control, the town of Gosnold forced the club to obtain and purchase licenses to privatize each of the stands. That edict all but closed fishing access of Cuttyhunk residents to most of the south-facing shoreline. Despite the disputes, many of the islanders were employed by the club, providing them with much-needed income.

The Cuttyhunk Association’s problems were not all associated with community relations; they had internal problems as well. Whenever you have a diverse group of powerful men who are each accustomed to having their way, you are likely to run into difficulties. The bylaws stipulated that members were allowed just one guest per visit, and that person was not eligible to visit the club again the same year. Another such regulation stipulated that all fish caught by members or guests became the property of the association. After the kitchen’s needs were met, extra fish could be bought back from the club, with the funds turned over to the general treasury operating fund. Another rule, unwritten but understood, was that no women were allowed at the club. Women and family had to take residence in local homes or on yachts anchored in the basin.

The Pasque Island Club

Unhappy with the Cuttyhunk Association’s rules, John Crosby Brown, a wealthy Pennsylvania barrister, gathered a handful of members and searched for a nearby location at least as productive as Cuttyhunk to establish their own bass club. They found just such a location a few miles to the east on the southeast corner of Pasque Island. After prolonged negotiations, the group purchased the entire island, which had been in control of the Tucker family for the previous 170 years.

Pasque Island is located between two of the most productive passages along the Elizabeth Islands—Quicks Hole to the west and Robinsons Hole on the eastern tip, which is where they erected their clubhouse. This placed the group at the epicenter of some of best striper fishing along the entire East Coast.

From 1869 forward, the members established a community that rivaled the much larger Cuttyhunk Club, with a main clubhouse and several other buildings to accommodate their families, the help, and the ghillies, who did the chumming and gaffing on the bass stands. The east end of the island had a protected cove and a stream that was dammed to permit the storage of live bait in the form of bunker and herring as well as lobsters. My research did not turn up the exact number of bass stands jutting out from the beach over the rocks, but I have fished there over the past several decades, and the locations of those on the southeast side of the island are obvious. Although the Pasque founders differed from Cuttyhunk on the specific rule concerning family and females, their regulations were very similar, and their control of the shoreline was as unyielding.

The Pasque Club took this control one step further by hiring a year-round caretaker to watch over the property. The club members and the entire Brown family enjoyed the good years when fishing was productive, but as the striper population began a downward cycle, members lost interest and operational costs increased. After 40 years as president and the driving force behind the club, John Brown died in 1909. His son, James, took over the leadership role. The Pasque club, because of its family hierarchy, persisted much longer than West Island and Cuttyhunk. It was not until 1923 that Brown purchased all the shares and property, disbanding the club. As the sole owners of this choice property, the Brown family continued to spend their summers there.

The Last Bass Club

The Cuttyhunk Club held on until shortly after World War I, when William Wood, a former member of the club, purchased all the holdings and used it as a family retreat until his death in 1925. His son took over and sold many of the houses that were club property, while maintaining the clubhouse and the accompanying historical artifacts in their original form.

The property was sold to the Moore family in 1943, who kept up the maintenance of the buildings and preserved all the historical documents and furnishings. Robin Moore, the famous author of The Green Berets and The French Connection, was one of the last members of the Moore family to make his home in the clubhouse. Moore claimed he did his best writing at Cuttyhunk, but his family, with whom he shared ownership of the property, wanted to sell.

In 1997, the property was sold to the granddaughter of Willian Wood, who returned the property back to the family of its previous owner. The Ponzecchi family has reopened the club as a bed and breakfast that has hosted fishermen from then up to the present day.

Newport’s Platforms

The craggy shoreline along Newport’s coastline was one of the most popular and productive striper haunts on the entire East Coast. The rock upon which we first fished the ocean was the foundation of one of the former bass stands of Brenton Reef. These rickety fishing platforms were erected by wealthy anglers to improve their odds of catching trophy stripers by providing a perch above the rocks and waves.

-Photo courtesy Mike Everin

Some of the best-known stands were situated along Ocean Drive from Brenton to Easton points, where the affluent residents along the Rhode Island coast enjoyed exceptional fishing. From the publication Some Fish and Some Fishing, “The largest striped bass of authentic record that I personally know of, taken with rod and reel, weighed 70 pounds. This fish was taken by Mr. William Post at Graves Point, Newport, R. I., on July 5th, 1873. It was a long, thin, and emaciated fish that would have weighed 100 pounds in normal condition.”

Graves Point in Newport was the site of several private bass stands that property owners along the ocean built in front of their homes. The Graves Point area was famous for its bass production from 1865 through the period of scarcity around the turn of the 20th century. Angler Thomas Winans (along with his nephew) accounted for numerous trophy stripers from the stands he erected in front of his oceanside home overlooking Graves Point. Accounts of their angling proficiency during a three-month period before the turn of the century had them landing 124 stripers with a total weight of 2,921 pounds, with the largest fish over 60 pounds.

The documentation of that catch was reported by Frank Gray Griswold, writing in the same publication in 1921. Griswold states, “I have known my father, the late George Griswold, who was a keen fisherman, to bring home before breakfast, four fish that would weigh over fifty pounds each, but that was in the [1860’s] at New London, where no bass are now to be found.”

Griswold goes on to lament the scarcity of stripers. “The fishing clubs have been abandoned, the stands have been destroyed by the action of the sea, and the waters are no longer chummed or fished, for the large striped bass have become a tradition of the past. This has been caused by excessive net fishing, for the bass, being a migratory fish, has been and is still netted along the full length of the coast both going and coming as well as when in southern waters, and the result has been fatal.”

I’m extremely grateful for the many “old-timers” who were aware of my keen interest in the bass clubs and their bass stands, and shared precious anecdotal and published information on them, including my friend and historian, H. Kib Bramhall, the late Charlie Tilton, and other Cuttyhunk and Vineyard sources. I also enlisted the assistance of the Fall River, New Bedford, and Newport public libraries, and the Little Compton, Fall River, Falmouth, and New Bedford Historical Societies, as well as the informative fish house crew from Sakonnet Point, Rhode Island.

Great story.Always wondered why all the steel was sticking out of rocks on the Brenton reef.Thought to my self a fish house.Amazing story. Thanks,Lee

Thanks for the wonderful article. My Dad was one of the last bait handlers on the Cuttyhunk stands. He and my Grandfather shared many a story about the fishing from there. It must have been an amazing experience with that many fish in the area.

Great story, Charley.

Great story, loved reading all the history of the bass stands. I’ve fished Martha’s Vineyard for 40+ years, and did the walk out on Squibnocket Point, stopping at the Bass stand location for a few casts, thinking what it was for the old timers, and then plodded along way out to the tip, across from Noman’s Island. Over the years fishing Squibnocket has.been more productive and enjoyable

than other spots.

In the 80’s n 90’s my buddy Peter and I used to walk out on Squibnocket point before dawn and fish from the rocks that are 20-30 yards off shore. Swimming out with rod and popper in hand we did quite well. Nothing huge but consistent. If we kept a fish the long walk back reminded us why releasing them was a smart idea.

Thanks for the fabulous history!

I live in RI and would often drive along Ocean Drive and imagine what these bass stands were like in their heyday.

Great story. Cuttyhunk is a great place. My wife and I had the pleasure of meeting Charlie Tilton over several summers. What a Great person and gentlemen he was. Thanks for the memory.

Love these retrospective pieces! Keep ’em coming OTW!

Great story on several levels. The opulence of the Gilded Age seems familiar in our current economic environment and the fishery seems to be facing new threats. It begs the question of the a linkage between unbridled capitalism and resource depletion.

In the modern world of fishing where history some times gets forgotten it is good to see historical fishing history being cataloged about how it all began in another time and place. Charles I may have missed it , however back in those days the New York Stock Brokers kept in touch with there offices, by bringing homing Pidgins with them to transact business and also tell others that the fishing was good . It is also noted that Charley Cinto passed away and perhaps it would be appropriate to enlighten the fishing world about your friend when time allows. I have my own memories Peace My friend

Very interesting story of the past . Poor line. I.e. Lining and not the rods and reels of today. When i started there was no mono just linen that had to be washed and dried on a line dryer. Was not as easy as it is now.

Great read, great historical lesson

I light have one of your grandfathers fishing luers. I bougjt a few from año antique dealer i have given most away if i have one left u can have it

Very interesting accounts of lost past fishing. They had an abundance of large fish for at least a while until overfished. We have advanced gear but fewer, smaller fish, still with overfishing and/or high fishing mortality

“Great Article” When there were a lot of Fish to be caught. Nowadays??? Love Newport and the Mansions. Back in the day, I used to run Ocean Drive. Nowadays I Bike it, but I still Love It!!! “The 5 Bridges” is a Great Bike ride in the Fall. “Tight Lines”

Thanks for the historical background. I’ve seen pictures of the stands, and the well-dressed gentlemen out on them, as well as the historical records for fish caught at the Pasque Island Fishing Club, and I can affirm that the weight/length numbers were very impressive, with many in the 40-50 lb range. As a youngster I was blessed to spend a couple of weeks each summer on Pasque, which my extended family purchased from Brown. I remember catching schoolies in the creek during the twilight, and standing in the current on the Pasque point with stripers practically bouncing off my ankles as I casted. The greatest thrill of all was catching a 40 lb’er while trolling at first light on the Vineyard Sound side with live Menhaden on the skiff of Walter Dixon, a local fisherman. We caught 1/2 dozen or so in the the 18-32 lb range but that big cow I brought in was something, as a 14 year old kid, I had never imagined! Right off the shore where all the stands were, too, by the way(don’t tell anyoneLOL)

Miko liked what you wrote about Pasque Isl. Tight Lines Bob J. VECK

Have the photo album (and some copies) of the Brown family album 1880’s to 1938. It shows a few stands and a lot of men alongside their

big ones. High Hook was 62 lbs in Sept. 1869(A. B Dunlap)

AWESOME ARTICLE OF FISHING DURING THE OLD DAYS……..GREAT JOB CHARLIE SOARES..I CAN READ STORIES LIKE THIS ALL DAY LONG

Thank you Captain Charley Soares for a great story about the old fishing days. I would like to say to all of you striped bass angliers if you want to read more of Charley’s fishing stories buy his book Living The Dream . I have this book in my collection its one of Charley’s best.